Large and imposing, the exterior of Luis Barragán's house reads like a prison wall. All that can be seen from the street is a massive flat, grey concrete wall three stories high that stretches from one end of the lot to the other, joining the buildings and creating a flush barrier. It had to be built this way. When Barragán designed his house in 1948, the Tacubaya district in Mexico City, where the house was built, was a dangerous place. Located kilometres to the west of Mexico City's historic centre, on the south side of a highway from Chapultepec park, the area was filled with peddlers, crime, abandoned buildings, and old paper factories. It was dangerous out here and far from Roma Norte and La Condesca, the affluent neighbourhoods to the south where Mexico City's upper class lived. To survive out here, Casa Barragán had to be tough. It had no choice. It would have been ransacked otherwise. The world outside was dangerous. Its walls, large and imposing, protected the private interior from an unforgiving public.

Artists — including artistically inclined architects — are known for breaking new conceptual territory. Sometimes that includes literal territory. In the case of Barragán, building a home in Tacubaya meant breaking the social norms coded by geography. It meant looking beyond the "acceptable" areas of Mexico City. Yes, there were physical and material risks for living out in Tacubaya. You could get mugged, your house could be broken into, your belongings could be taken from you. But perhaps more consequential, particularly for an up-and-coming member of Mexico's cultural class, were the social risks. Shared geography comes with shared group membership, especially if that geography is elite. To break out of those boundaries meant distancing oneself from the social group, an especially risky maneuver in Mexico's profoundly stratified social structure of the 1940s.

But artists do what artists do, and Barragán was an artist with an architect foil. As every artist knows, any risk — especially the social risks invented by Mexico's upper class — is counterbalanced with a reward of equal measure. For Barragán, the reward was freedom. Freedom from the restrictive norms placed on his work. Freedom from being forced to please unpleasant people. Freedom from the concept of "acceptable". Like a refugee escaping a dictatorship, Barragán could create his work on his terms out in Tacubaya. He could live as he pleased.

Barragán was no stranger to escapism. Born in Guadalajara in 1902, Barragán quickly bumped up against the restrictive social norms that dominated Mexican life outside of Mexico City's artistic enclaves. At the time of Barragán's youth, Guadalajara was a trade centre for Mexico's ranching and agricultural class that cultivated the plains of Jalisco. This economy, coupled with a social and political structure steeped in colonial catholicism made life for a creative individual like Barragán difficult. He had to leave in order to fully embody his interests and desires. There was no other option. And leave he did. First to Europe — Spain and France — and then New York, where he suctioned up all interesting ideas and experiences offered to him. It was on these trips that he was introduced to the writings of Ferdinand Bac, made friends with Mexican mural painter José Orozco, and even briefly met Le Corbusier. His world expanded, having travelled, he then returned to Guadalajara, and Mexico City soon after, full of ideas.

What emerged from a repressed upbringing was a profound reverence for simplicity and serenity. Both have reparative functions from ideological oppression. Colour, texture, light, shadow, and form became Barragán's nurses, mending him back to health. In Casa Barragán, light is treated like liquid diamond — a precious stone that is carefully unearthed by the architecture, but also one that ebbs and flows with the hours of the day as well as the seasonal shifts. The entranceway is dark and confined, but five steps into the house reveals an interior studio bathed in soft light, where Barragán would work with his design partners for days and days.

"Is this his whole studio?" I asked the docent during our visit.

"Yes, Barragán worked with a small group of friends. Most of his well-known works were created here in his home studio."

A refuge for his private life and a refuge for creative work, both under assault from the outside. "Mi casa es mi refugio" Barragán once said in an interview. The need for isolation was of professional and existential importance. But it wasn't just work that took place inside Casa Barragán. A quick turn from the studio and the house opened to the outdoors in the form of an interior courtyard, a place of reprieve. Here, the walls reach between one and three stories high, forcing the occupant to crane their necks back to see the sky above. Thin vines flow down from the wall tops, bursting forth from unknown origins. Because the space is bounded by cubic forms, the sun's rays slice through about one-half of the interior void, creating a sharp contrast between light and dark. In the lit corner, a shallow fountain layered with dark slate underneath acts as a cooling device for the entire space. The fountain is proportioned to the size of a human body as if requesting a full-bodied plunge without literally affording it. In the shadowed corner, a cluster of Mayan pots, ancient yet easily confused as modern; quintessentially timeless.

Why, between work and living spaces, would Barragán interject a seemingly frivolous courtyard? There is already a garden on the other side. Why dedicate more space — space that is at a premium — to water, light, shadow, pots, and plants?

Deciphering Barragán's architecture is a means of deciphering Barragán's psyche. If movement and occupation in the urban realm — in cities — can be interpreted for conceptual meaning, so too can the design of a house. Especially if the house was designed to be occupied by the architect himself. Interjecting a courtyard between the living and professional spaces can be interpreted as a meaningful conceptual distinction between reprieve and production. Through this distinction, each of those two programmes is accentuated. Although completely open and exposed, this interior courtyard is more of a gate.

On the other side of the courtyard, through a small door, is the Casa's garden. The garden is expansive. On plan view, it takes up nearly half of the whole lot. But unlike the open courtyard, the garden is full of thick plants and trees that obscure sightlines and block the sun above. In this garden, there are multiple hidden alcoves to take refuge in.

"He would hide in here." An old friend of Barragán, who was with us, said.

"If you didn't find him in the house you could find him in an alcove in the garden, sitting, reading or writing."

Refuge within a refuge, I remember thinking. Like peeling an onion.

Adjacent to the courtyard was the dining room, where Barragán would host guests. A long, thick, Mexican oak table stretched nearly the whole length of the space, which was painted a cobalt hue of dark yellow. Light is given careful treatment here. Instead of harsh overhead fixtures, two clusters of steel orbs placed on top of the table curl the outdoor light around the room, creating a soft, steely glow. Around the corner from the room is the stairwell that leads to the second floor. In contrast to the subdued lighting conditions of the dining room, the stairwell is filled with crisp light shining directly down from a skylight above. We make fun of moths for the way they are automatically pulled toward lamplight like mindless spawns, but here humans are no different. In this stairwell, it's impossible not to feel an upward pull, toward the light.

The second floor of Casa Barragán has a different composition than the ground floor below. Up here, formal innovation is traded for domestic predictability. Two simple bedrooms flank each side of the house, one for guests and one for Barragán himself. In the guest bedroom, massive square chunks of the exterior wall can be pulled open and angled at will, allowing for sunlight and fresh air to fill the room. The space's primary window is massive although the view is shaded by trees outside, which sway gently in the wind. As was the case in the dining room, steel orbs and canvases with reflective gold paint reflect the light around the room, creating a soft and ambient atmosphere.

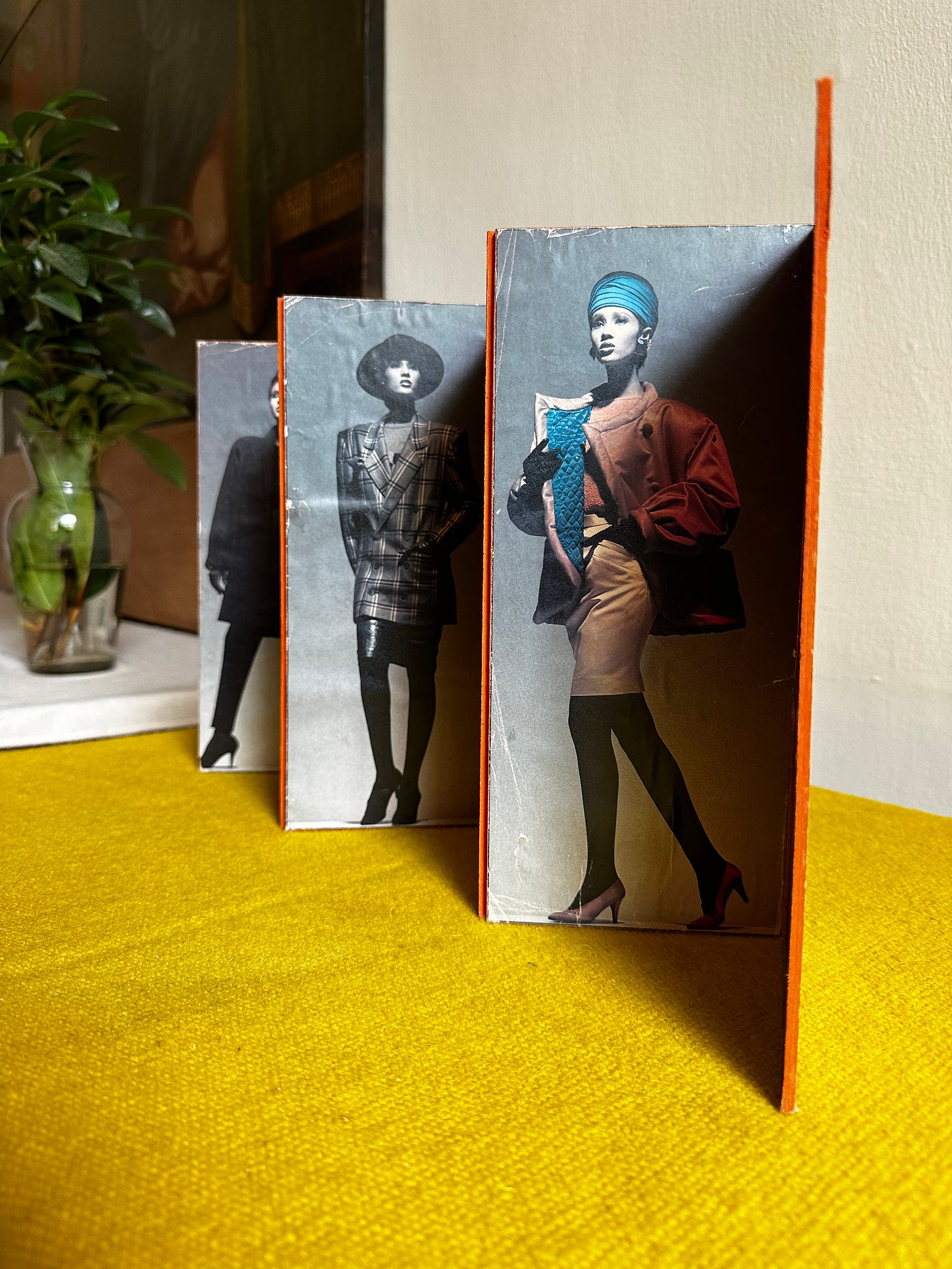

A short walk down the hall from the guest bedroom leads to Barragán's bedroom, a space of almost identical size. In this room, objects are positioned in accordance to a strict logic. A thin, single bed — Barragán's own — sits near the centre of the room underneath a thin, demure catholic cross hung on the wall. Barragán, after all, was a deeply religious man. He also worshiped God. He also worshipped beauty. Across from the bed on top of a dresser, a folding montage of his favourite supermodel, Iman. Beside that, a stone statue of a horse mid-stride, sturdy and virile.

Much has been said about the "type" of man Barragán was. According to the facts, he never married. He socialized with Mexico's creative class, including an insular cluster of gay men. He devoted his life to the production of beauty. He painted his buildings bright pick and dedicated entire courtyards to blossoming Jacaranda trees. Some theorists have read his private residences as "gay-friendly". Casa Pedregal was advertised in 1937 as a "modern residence for a family consisting of two persons". It features two separate staircases that lead to separate sections of the second floor that are completely sequestered from each other; one for the servants and the other for the owners, guaranteeing their privacy. So what? You might ask. So what if he liked these things? So what if he spent time with those people? So what if his buildings looked like this? What does any of that mean?

"Rumours." Barragán's old friend said to me when I asked him about some of these things I had read.

"You are reading rumours. He never married. That's it."

Fine, I remember thinking. Fine. Though curious and desperate to know more about Barragán, I won't ask about it. The curtness of his response, replicated by multiple other docents, communicated to me that the Mexican story keepers were prepared for a quick reply, as if they had been confronted with these observations before. I could feel a tension emerge between the old friend and I. He was aware, it seemed, of the push and pull between Mexican machismo and Western progressivism. Between the past and the present. Between a story and the truth. Between facade and interior.

"You know" he turned to me.

"He never married, it's true. He dedicated his life to beauty, that's also true. What that means, I don't know. I'm not certain we can use the words of today to explain the phenomenon of yesterday. When I met him, I knew he existed in a zone of indeterminacy. I knew that. If anything, that's what drew me to him."

A zone of indeterminacy. What an interesting concept, I remember thinking. A conceptual space where one is allowed to exist without labels. Where one could live as they please. Where one could be free.

We continued on through Casa Barragán. A slim set of stairs led through a small door that opened to an L-shaped rooftop courtyard. On one side, the stone walls are covered in white paint. In another corner, an amber-tweaked orange. Then, pink — a fiery pink — covered the final corner. The colours, along with the height of the walls, created an architectural effect I had not yet experienced up until that point. Three walls of differing heights crisscrossed against one another, creating a collision of colour that culminated in one, solitary pillar reaching 20 feet upward toward the sky. It felt as though the entire house led up to this point, this climax. And I felt as though I had seen this space before, but only in my imagination. A sacred refuge against a harsh world, where new meaning emerged from a collision of colour, texture, light, shadow, and form. It is an exalted moment in a sprawl of urban regiment, bereft of burdensome social norms and expectations. It is Casa Barragán's most intimate moment, as well as an instantiation of Barragán's intimate interior.

Movement in and occupation of the urban environment has metaphorical connotations, sometimes more meaningful than the physical acts themeselves. Architecture, then, is the discipline where man takes control of his metaphors. At Casa Barragán, the architecture is a fortress. A fortress against a dangerous neighbourhood in Mexico City that can be read as the counterpoint to Mexican society at the time it was built. But more than that, it is also a fortress against the harsh and restrictive social norms that dominated the country. Of machismo mixed with strict catholicism. The same restrictive norms that forced Barragán to flee Guadalajara in his youth. Through architecture, Barragán built a refuge for himself and his friends. For his private life as well as for his psyche. Bright pink stone, a hard foil for a soft interior. It had to be built this way. He had to be built this way.