The following is an essay on the Ryōan-ji rock garden in Kyoto, Japan, which I visited in 2016, and the role it plays in structuring the abstract concept of uncertainty.

Ryōan-ji, The Temple of the Dragon at Peace, is a Zen temple located on Kyoto's northwest edge, on the border between the city and the forest. Built by Rinzai Buddhist monks in the fifteenth century during the Edo period, Ryōan-ji is at an appropriate location for a Zen temple. Out here, the sounds of the city are replaced by bird calls and a deep hush of the blowing wind on the trees. Out here, it's impossible not to think of the forest beyond the temple walls, even if only as an abstract entity; dense, dark, and expansive, without a clearly defined shape or form. Out here, at the threshold between city and forest, objectivity is exchanged for imagination.

A large gate marks the entrance to Ryōan-ji. The gate's sheer size mandates deference, rendering pilgrims out of all who enter. A stone path leads from the gate to the hōjō, the temple's main building with three separate rooms for study, meditation, and sleeping. Three sliding fusuma doors covered in landscape scenes painted in the traditional Edo style separate the three rooms. In the traditional Edo style, negative space plays a prominent role in scene composition. The subjects of scenes, whether they be people or landscapes, are painted in dark ink, while the background canvas — the negative space — remains untouched, shining a bright white, retaining a visual presence despite an absence of subjects. This effect gives traditional Japanese paintings a certain elegance that is unreplicated in Western art. In Western art, subjects are often well-lit against darker backgrounds, clearly indicating who and what the viewer should attend to. In traditional Japanese paintings, it's less clear. The dark subjects in the foreground draw your attention, but the viewer's eye will inevitably wander into the soft, milky background.

(1) Right screen of the Pine Trees screens (Shōrin-zu byōbu, 松林図 屏風). (1595). Hasegawa Tōhaku.

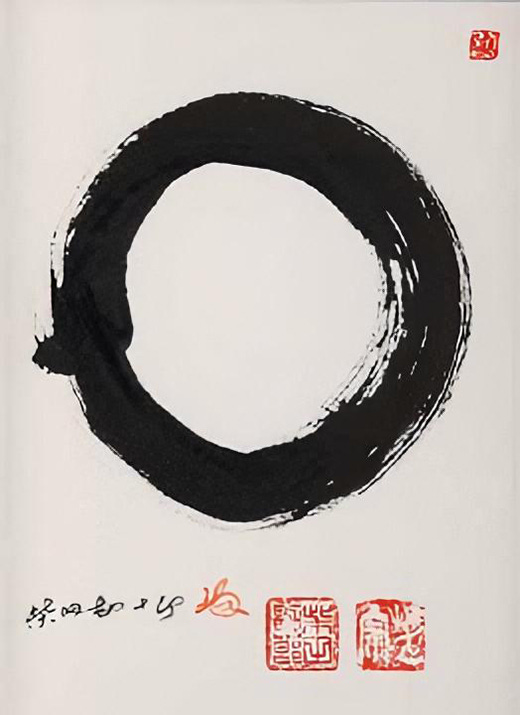

Negative space plays a prominent role in Eastern philosophy, too. In Buddhism, negative conceptual space is the mechanism for enlightenment. To attain enlightenment practitioners must destroy their "ego-consciousness" which continually seeks certainty. Certainty, though, is impossible according to Buddhism. The world is too disordered, and the mind too feeble, to ever arrive at certainty. The ego-consciousness suffers because it attaches itself to any type of fabricated certainty, making its integrity contingent on imagination. To prevent this type of suffering, Buddhism promotes the Non-Self, which is a state of being that is unable to attach itself to material objects or fabricated certainty because there is no self with which to attach. The Non-Self is comfortable with uncertainty. The concept of the Non-Self is embodied in the ensō, a type of painting common in the Buddhist canon. The ensō is a circle that is hand-drawn in one brushstroke. It represents a moment when the mind is free to let the body create. Ego-driven knowledge is absent, leaving only an embodied presence to guide the brushstroke. What results is a figure that can communicate more about the personality of the creator than a resume ever could. Buddhist practitioners in Western countries have adopted the ensō as a metaphor for the Non-Self by noting it takes the same shape for a null, or zero, numerical value. Odd, they note, that we have a symbol representing nothingness.

(2) Ensō. (2000). Kanjuro Shibata.

The Non-Self's comfort with uncertainty is a difficult concept to grasp, especially for Westerners trained in philosophical schools of thought that preference objective knowledge derived from ego-driven rationality. For Westerners, uncertainty is something to be conquered, not acquiesced to. Yet, the tools with which we try to conquer uncertainty are feeble in relation to reality's uncompromising complexity. Phenomena in our lives will inevitably surprise and confound us no matter how hard we try to explain them using the crude epistemology of rationality. Westerners — and people in general — are much more likely to render a judgment about an ambiguous situation instead of acquiescing to uncertainty. It takes wisdom to withhold judgment. To be comfortable with uncertainty. It takes a life of hard lessons learned from real consequences of incorrect judgments. Or, if fortunate, exposure to a schema from which the process can be modelled.

The Ryōan-ji rock garden provides such a schema. Located adjacent to the hōjō, the rock garden is a ten by twenty-five metre rectangular space filled with a sweep of soft, milky white pebbles raked into linear patterns. Placed within the space are fifteen stones of different sizes. Some lay flat and long, barely perceivable, like the backs of whales surfacing for breaths of fresh air. Others are tall and stately, like the limestone mountains of Guilin, China. Some are surrounded by brown-green moss.

At first glance, there doesn't seem to be anything noteworthy about the Ryōan-ji rock garden. Defined using an ego-driven rationality, it's certainly just a bunch of rocks placed on a stretch of pebbles. Adopting an Eastern philosophical stance towards Ryōan-ji is more productive. From this perspective, the negative space in between the rocks takes on new meaning, making the overall composition appear harmonious, inviting meditation from the hōjō's veranda. An important design feature of the rock garden emerges from this vantage. Despite having fifteen stones, only as many as fourteen can ever be seen from any one perspective. This is because the larger rocks are placed in such a way that they occlude the smaller rocks. It doesn't matter if you move all the way to the left or to the right of the veranda, you will never see more than fourteen. This configuration of stones produces an interesting visual effect, and it's meaningful to think about the mathematical calculations the designers would have completed to achieve it. However, reducing the meaning of this maneuver to "merely mathematical" belies its abstract import, particularly as it relates to the Zen Buddhist philosophies infused in the garden's design.

It is through the constant occlusion of at least one stone the Ryōan-ji rock garden provides a schema for the Buddhist concept of comfort with uncertainty. Bright, clear, and stable vision is an embodied experience often used to metaphorically describe the metaphysical concept of certainty. We "see the truth clearly" when we understand something, or an argument "is murky" when we can't make sense of it, or we "overlook" details, or "focus in" on a solution. At Ryōan-ji, the designers intentionally provide viewers from achieving a total view of all of the stones in the rock garden, playing with our sense of certainty about the composition of the stones. Ryōan-ji rock garden is uncertainty instantiated. Uncertainty a necessary condition of the phenomenology of meditating in front of the rock garden. In this way, meditating at Ryōan-ji can be used to train one's psyche to be comfortable with the phenomenology of uncertainty, which is a foundation skill of all Buddhist practice and a life lived in pursuit of Buddhist principles.

(3) The Ryōan-ji Rock Garden.